Minding the Gaps

On location-based VR, the art of "becoming," and a family of worms living in an apple.

One of my abiding fascinations as a creator and thinker is using virtual reality within a curated story-event. The piece that birthed this fascination for me is Draw Me Close, a VR/theater piece for one audience member that I experienced at the Young Vic in London back in 2019. It’s manifested in my own practice through the ongoing development of The Usses, a play that asks audiences to don VR headsets at various times to engage with onstage characters by “becoming” different parts of the landscape/setting.

The idea of “becoming” is central to what I think is so special about VR’s affordances — perhaps even more so than in IRL immersive work. In Immersive Storytelling for Real and Imagined Worlds, Margaret Kerrison emphasizes the importance of determining wish fulfillment: the special interactions and possibilities an experience grants its audience. That’s closely aligned with the “becoming” of VR: how it can help shed the character of “me” in order to take on a new sort of me, in a new sort of reality.

My experience, though, is that VR can manipulate your senses into more powerful “becomings” than purely meatspace immersive can. Draw Me Close, for example, had its audiences become a younger version of the piece’s creator, Jordan Tannahill, and move through various stages of his relationship with his mother as he grows. The mother is played by a live performer wearing a motion-capture suit, and you see her in your headset (as well as the rest of the shifting environments) in a pen-on-white-paper aesthetic style. When she hugs you, draws with you, tucks you in, and says goodbye, I find the aesthetic distance of the headset allowed me to fall deeper into the character of Jordan than a similar IRL experience would’ve. On top of it all, you hear periodic monologues from Jordan’s POV through your headset…providing a feeling that these reflections are coming from your own mind.

Draw Me Close had no shortage of VR-specific visual delights — most notably the “re-drawing” of the sets between scenes, as time passes — but it has staying power for me because of how it made me feel like Jordan, and (perhaps more importantly) like the son of Jordan’s mother. From that grounding, the piece was able to unfold its story through me in a way that felt truly medium-specific, masterful, and new. Jaron Lanier, one of the godfathers of VR, crystallizes all this better than I could in The Dawn of the New Everything:

I’ve always thought that when VR matures someday, then an artwork, a lesson, or a conversation in VR will not be made up of a virtual place you visit, as current imagination usually holds, but a form you turn into.

Whether the form you take is another person, another type of being, or even just a “slanted” version of yourself, I believe from my experience with Draw Me Close that this is where great work in this new-ish medium will spring from. I take Lanier’s words as an exhortation to use VR towards creating new, full forms within its users — and having those forms be the bedrock upon which to tell new stories.

All of this to say: I think location-based VR (LBVR) experiences are an ideal place for this type of work to flourish. LBVR allows creators a lot more control over shaping the sensory inputs that allow a feeling of “becoming” to emerge than most at-home VR set-ups currently do. Full-body mocap sensors, 1:1-mapped1 experience-specific items, haptic-enabled set pieces (like shaking platforms), large spaces for roaming, and simultaneous sharing of a digital environment amongst multiple IRL participants are just a few of the affordances made much easier in this creative format.

In the past year I’ve been to three different LBVR experiences, offered by three different companies. I was amazed by how different they are from each other: how they draw influence from different artistic mediums, how they approach narrative in vastly different ways, and how — most importantly, I think — they take completely different approaches to fashioning what you “become” when you slip inside their headsets. I think this last point is especially illuminating for VR’s potential future trajectories.

SPOILER ALERT — details about the following experiences: Sandbox VR’s “Seekers of the Shard: Dragonfire”; Dreamscape VR’s “Alien Zoo”; and Hypergate VR’s “Temple of the Diamond Skull”

In Sandbox VR’s Seekers of the Shard: Dragonfire, you become — in a word — a fighter. While you are given the option before the experience begins to choose amongst different battler classes and avatars, the general experience is the same: you fend off waves of skeletons, orcs, and such by swinging a weapon with one hand and casting spells with the other. At one point, you are given the option to take one of two different paths towards an inevitable showdown with the titular dragon…but my heart was racing so fast from the combat that I honestly couldn’t even track the story points that made me want to go one direction or the other.

Dragonfire felt inspired by combat-based video games; while you can’t “die” per se, you can be damaged enough to enter a sort of ghost mode, which requires a fellow player to put their hand on your shoulder to resuscitate you. You also see a leaderboard at the end that tallies how much damage each player doled out. Beneath these game-inspired touches, though, is the underlying wish fulfillment — which I took to be the thrill of combat, a state of battle heightened by the fact that, when you’re “damaged,” haptics are activated on the front or back of your chest pack. If you’re made to “become” anything within Dragonfire, it’s an adrenaline-fueled and instinctual version of yourself.

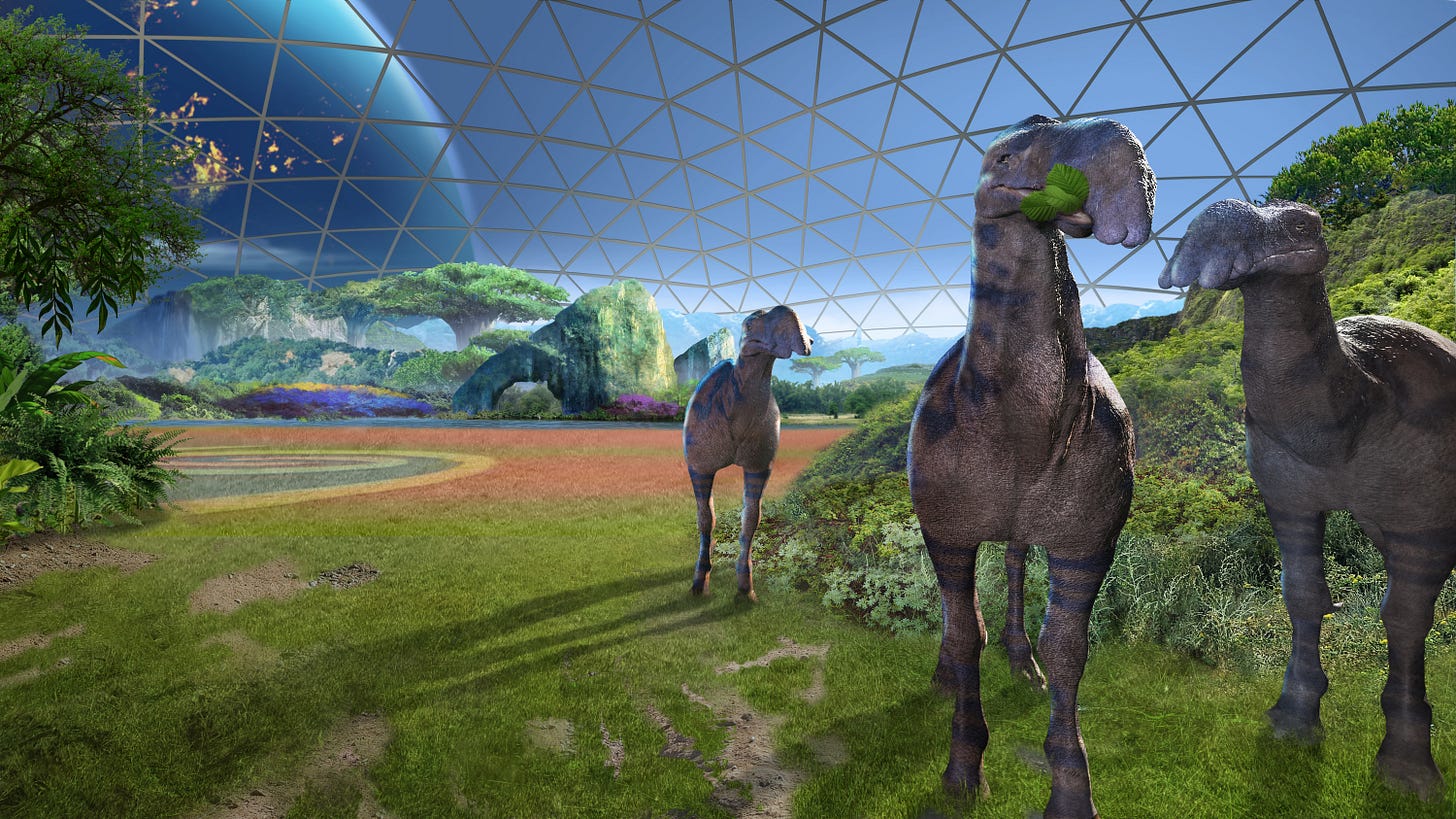

You also have the option to choose an avatar in Dreamscape VR’s Alien Zoo, but this choice is similarly cosmetic. Players are cast within this experience as humans visiting an alien zoo (surprise!) on a distant planet, where you meet a variety of curious beasts and are given the chance to interact with them. These interactions are clever and use VR affordances in really interesting ways; you can pet one of their heads, for example (a 1:1-mapped animatronic), and another alien has a miniature reflection of the player’s avatars on the surface of its single massive eye. One of these aliens does turn out to be threatening, and you are called upon to subdue it — but that experience feels like a jag of excitement within a general vibe of reflection and wonderment.

Of the three LBVR experiences I had, Alien Zoo was by far the most polished. Yet I think that polish was delivered with a specific POV towards participants: that they would be experiencing a new world, instead of experiencing a new self. This was reflected in the tight control the experience had over its participants at each moment: the tour guide, via voice-over, gave instructions for how to interact with each new element introduced. This sort of “frame-by-frame” control made me feel Alien Zoo to be deeply influenced by filmmaking techniques, in contrast to Dragonfire’s more game-influenced approach to interactivity.

Temple of the Diamond Skull was by far the least polished of my LBVR experiences. Our avatars looked like discount-rack Halo characters, and had no relation to the world we were in whatsoever. We even sat through a game-engine load screen just before we started. But despite all that, I have to say: this was the experience that made me the most excited for what LBVR could do. And that’s because it was the most effective of the three at making me become someone new.

All the story content of Temple of the Diamond Skull is contained in its title: your goal is to navigate through a temple in order to find a diamond skull. There are a scattering of puzzles along the way, as well as some skeletons and skittering creatures to provide little jolts of creepiness, but the majority of the experience is navigating through dark tunnels with a torch in your hand. This navigation, however, was quite robust, for a couple reasons: firstly, that Hypergate VR’s Santa Monica space was much larger than the other two LBVR spaces I visited, and secondly, it privileged the core experience over creating a sense of total immersion.

By that last point, I mean that the docent at Hypergate gave us a simple instruction: don’t lean on the walls in the experience, because the walls don’t really exist. This asked for a suspension of disbelief that wasn’t present in either of the other two experiences; Dragonfire is played in a contained space that had no walls, and Alien Zoo unfolded on a moving platform where the rails and everything between them were mapped 1:1. I touched the “walls” in Temple quite a bit, because the temple pathways are narrow and winding. But that’s of course what you can do when you say “Just believe the walls are real”: you can create a compelling and absorbing maze that doesn’t have to conform to physical space (or the laws of physics, even). And precisely because the maze was so absorbing, I found myself not caring at all when a stray hand grazed through a stone pillar.

This revelation led me towards a deeper truth about LBVR: despite how the technology helps create a close simulation of reality in many ways, there is inevitably some sort of disbelief-suspension at play. In Dragonfire, we agree that rumbles on our chest packs will replace being actually hurt by the bad guys (thankfully!); in Alien Zoo, we’re okay with flashlights becoming visible on our platforms only when the experience allows us to use them. Not only do we permit these sorts of suspensions…in my experience, we actually love them!

Why? Perhaps because the VR-unique combinations of combat + localized haptic feedback in Dragonfire, and object-appearance magic + interactive items in Alien Zoo, dazzle us enough to not make us think too much about how “in-world” they are. But I also believe it’s because these moves often give us a gap between what the VR-mediated version of the experience is, and what the IRL version would be…and the way we fill in that gap is inherently satisfying.

Because I’m a playwright, I can’t help but think of analogues from my native art form. When audience members go to the theater to see a play, there’s an agreement made that what they’re going to see is not going to adhere to reality — and, because of this, they will be called on to use their imaginations to build the story and its meaning in collaboration with the performance. Here’s an example. Say a play starts with a spotlight shining on a lone red apple. Then, a moment later, four actors come onstage dressed as worms, talking about how much they love their shiny red new home since they patched up those pesky holes they used to get in. At that moment, audiences will build a new version of reality: they’ll see the worms on the inside, and their apple home from the outside, at the same time. The play doesn’t tell the audience this, though — it makes a gap that is shaped in the right way for the audience to fill it in naturally.

Because there’s also a level of agreement to suspend disbelief, I think similar sorts of gaps can be fashioned in LBVR…but I think they exist less in the distanced imagination of theatergoers than in the visceral experience of the user. It could be formulated as this question: “How much space is there between what this experience puts in place, and what the player can fill in through their own experience?” I believe shaping this space is key to creating a feeling of “becoming” within VR.

In Temple of the Diamond Skull, you are given a setting (the winding labyrinth of an ancient temple), a few tools (a torch, and a plank to help you across an abyss at one point), and an objective (get to the end). This creates massive gaps between what the experience conjures and your own moment-to-moment experience: meaning, lots of space to fill in the minutiae of your personal adventuring experience (“What’s around that corner? Did you see a shadow just then? I hope more rats don’t freak us out!”).

With Dragonfire and Alien Zoo, I found the gaps between what I could do and who I was becoming to be quite narrow. In Dragonfire, I was either attacking or dodging at nearly every moment — doing what I could to stay alive with the weapon I wielded. The gap that did exist was more emergent, made through how I collaborated with my fellow combatants: “I’ll take the ones on the left!” and “Get over here! This side’s safer from the swinging blades!” Alien Zoo had almost no gap to speak of: the interactive affordances of each moment were very tightly controlled and dictated, to the point that there was no space on the tour for me to be anyone but myself.

It’s possible to make LBVR that both has these gaps and (unlike Temple) a richness of narrative. I know it’s possible because Draw Me Close did it. Despite having a linear script that follows a prescribed story, Draw Me Close carved out purposeful gaps to fill in the space between yourself and the character of Jordan: an opportunity to draw on a piece of paper and talk to your mother about it; an impromptu conversation while being tucked into bed when you’re sick; the opportunity to give your mother a hug, if you wish, after she reveals a piece of tragic news. These could all be seen through one lens as simply moments of interactivity, but to my eyes they’re designed with more precision than that. Each gap fills in who you are in relation to this world, more and more. What you draw alongside your mother makes a literal mark on the virtual world, by staining the carpet in a way that re-emerges at the end of the piece; how you speak to your mother as she tucks you in, or how you hold her in a devastating moment, calls upon you to fill in the visceral minutiae of “becoming” her son.

It’s worth saying here that Alien Zoo and Dragonfire probably had much different experiential goals than the “gaps towards becoming” that I outline here! I should also say that I enjoyed both of them tremendously. What I’m trying to get at is the idea that LBVR has the potential to give us something very special: beyond VR gaming, or interactive short films, and into territory that leaps from being a genre-influenced adventure to actually being an adventure! I think that’s worth thinking about as immersive creatives, because I think that’s where VR will be able to make its true mark as a new art form.

I use “1:1 mapping” to refer to IRL objects that take a similar digital shape in VR, so that touching/interacting with them within the headset feels “real.” In Draw Me Close, for example, the bed you’re tucked into is an IRL bed that’s 1:1 mapped within your headset as a digital bed.